20th Century:

Kitty Hawk to Global Hawk

"The Fastest Man on Earth," a title Glenn Curtiss earned by clocking 136.3 mph on his V8-powered motorcycle, was also the "Founder of the American Aircraft Industry" and the "Father of Naval Aviation."

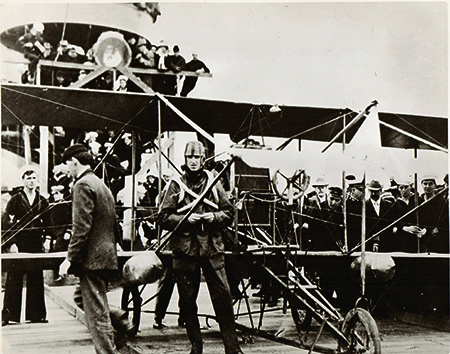

Demonstration pilot Eugene Ely and his Curtiss Pusher biplane before taking off from the USS Pennsylvania on January 18, 1911. Earlier that day he landed on the ship's deck to complete the first landing on a warship. Ely's flying attire included rubber inner tubes worn around his shoulders as a life preserver.

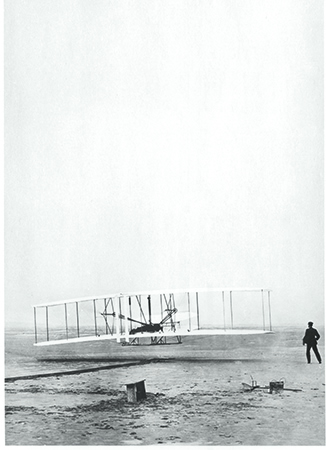

Glenn Curtiss and Wilbur and Orville Wright were self-taught engineers who separately took on the challenge of manned flight in the early years of the 20th century. The Wright brothers' success on the windswept dunes at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, on December 17, 1903, is well known. Less often highlighted are Glenn Curtiss' numerous inventions and achievements associated with the development of aviation, such as the first dual pilot control and the first radio communication with an aircraft in flight.

Working in the secrecy of their Dayton, Ohio, bicycle shop, Wilbur and Orville built a wind tunnel in the fall of 1901 to repeatedly test and refine their key invention: the wing-warping system that enabled their triumph at Kitty Hawk. They conducted two years of tests on variations of their system, initially using kites and gliders, in the wind tunnel as well as in real-world conditions, before piloting their own fragile plane into history. Their 1906 "flying machine" patent of the wing-warping system marked a milestone in the annals of American engineering and invention.

Glenn Curtiss also came to aviation via the bicycle business; in his case it was a small shop on the town square in Hammondsport, New York. An intrepid bicycle racer with a love of speed, by 1901 the 23-year-old Curtiss was strapping small engines onto bicycles and had soon graduated to building motorcycles. His engines first caught the attention of dirigible makers, and then, in 1907, a group of aviation enthusiasts led by Alexander Graham Bell became determined to build upon the Wright brothers' triumph. It didn't take them long. This period of close collaboration with Bell's Aerial Experimentation Association led to Curtiss' subsequent winning of the 1908 Scientific American Trophy for a flight of more than one kilometer in a straight line and his 1909 victory in Reims, France, outperforming the Wright brothers' planes.

While much of the early era of aviation was marked by competition among the Wright brothers, Glenn Curtiss and other industry pioneers, the seeds of partnership also played a key role in the evolution of aviation and the Curtiss-Wright Corporation from early on.

A History of Partnership with the Military

The Wrights and Curtiss each pursued early partnerships with a customer that proved instrumental to the development of aviation and aeronautics: the U.S. military. The Wrights secured an order from the Army Signal Corps in 1909, marking the dawn of military aviation in America. The next year, Orville Wright opened the first Wright Flying School on a site in Montgomery, Alabama, that later became Maxwell Air Force Base.

Curtiss concentrated his attention on the Navy. He had experimented with a design for a "hydro-aeroplane" on the Finger Lakes of New York in 1908 and was convinced he could build a working seaplane. By January 1911, he made the first successful flight of a practical seaplane, taking off from and landing on water. That May, the U.S. Navy ordered its first two planes from Curtiss. He also sold seaplanes to the navies of Russia, Germany and Japan over the next two years. More impactful was his offer of free flying lessons to officers in the U.S. Army and Navy. By the onset of World War I, the concept of naval aviation was embraced, and Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company began producing more than 100 aircraft per week.