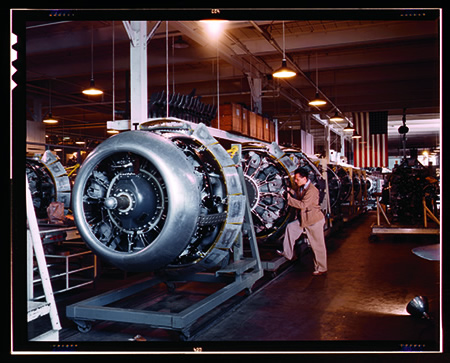

A worker prepares a Wright Cyclone radial engine for installation on a North American B-25 bomber. Initially developed in the 1920s and continually improved upon over the years, the Cyclone was a proven performer in both military and commercial markets. The engine was extremely popular with the military in World War II.

Roaring into the 1920s

The U.S. commercial aviation industry developed in earnest following the Allied forces' victory in World War I. Advances in plane, engine and propeller designs continued throughout the 1920s. Spurring the advances were promotional speed races held throughout the United States and Europe. By 1923, a Curtiss racing plane powered by its water-cooled D-12 engine set a world speed record of 266 miles per hour. Realizing that such racers were prototypes for the next generation of fighter planes, the military also stepped up orders in the latter half of the decade.

Wright Aeronautical's engine business led the next wave of industry development in the 1920s. The company focused on the more dependable air-cooled radial engine, yielding the Whirlwind and Cyclone engines, both hugely influential air-cooled engines in the interwar years. With Charles Lindbergh's dramatic 1927 solo crossing of the Atlantic Ocean in the Spirit of St. Louis, a custom-built plane powered by a single Wright J-5C Whirlwind radial engine, commercial aviation became widely accepted as a reliable means of transportation.

During the early years of manned flight, the Wright brothers' successor companies were known principally for producing superior engines. The Wright-Martin Aircraft Corporation produced more than 5,800 Hispano-Suiza aircraft engines, popularly known as "Hissos," in support of the World War I effort. While their corporate history took on many names as various investors and inventors lent their expertise to the development of aviation, the most productive years were achieved and memorialized as the Wright Aeronautical Corporation.

Curtiss' corporate offspring, on the other hand, took the lead in producing aircraft, notably with the JN-4 "Jenny," as well as its H Series of "flying boats," or seaplanes. By the end of World War I, Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company had employed 18,000 and produced more than 10,000 planes and engines. However, Curtiss had not abandoned the engine business by any means — in 1917, the company sold the first engine to an airplane maker named Bill Boeing.

The movie Flying Tigers was released in 1942 and starred the P-40 along with John Wayne, who was appearing in his first war film.

Designed for making swift dives with heavy payloads, the SB2C Helldiver was particularly effective in World War II's Pacific theater.

The Founding of Curtiss-Wright

Over the years, Curtiss and the Wright brothers, ever the inventors, had essentially given over control of the production and manufacturing companies they developed to pursue other interests. Forces much more sweeping than the rivalry between the Wrights and Curtiss — including the popular mania generated by Charles Lindbergh's solo transatlantic flight and the booming late 1920s stock market, particularly in aviation shares — eventually caused the merging of business interests.

In 1929, a group of New York investors merged 12 corporate entities, including Curtiss Aeroplane and Wright Aeronautical, to form the Curtiss-Wright Corporation, making it the largest aviation holding company at the time. It was also publicly listed on the New York Stock Exchange, where it still trades today. The merger created a vertically integrated aviation powerhouse that included plane and engine manufacturing, airline operations and services, and airports.

Shortly thereafter, the aviation industry suffered severe cutbacks during the Great Depression, as did virtually every segment of American industry. However, there were many areas of strength for Curtiss-Wright. In particular, continued improvements in the Cyclone engine led to its use on the Douglass DC-3, the workhorse commercial plane of the era. By mid-decade, the engines were producing 950 horsepower. Company engineers continued to boost the performance of existing product lines, including propellers. The variable-pitch propeller, the hollow-steel propeller and the concept of "feathering" — the disengaging of a propeller from an inactive engine to prevent engine rotation — were all performance innovations that came to market in the 1930s. Military orders gradually returned, notably in 1934 for nine-cylinder engines, two mounted on each wing, to power the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, and in 1937 for the Curtiss P-36 Hawk Fighter Plane.

World War II

The advent of World War II created an unprecedented surge in aircraft, engine and propeller design and production. It was long overdue. On September 1, 1939, the U.S. Army Air Corps had just 2,400 aircraft of all types, and many were obsolete.

The Curtiss-Wright P-40, an upgrade of the P-36, went into service in the summer of 1940 as the first-line fighter of the U.S. Army Air Corps. It was essentially the only fighter the United States had throughout 1941 and 1942. The most famous P-40s were the Flying Tigers, which were flown in China by the American Volunteer Group. More than 13,700 P-40s were produced, and they served in the air forces of 28 countries during World War II.

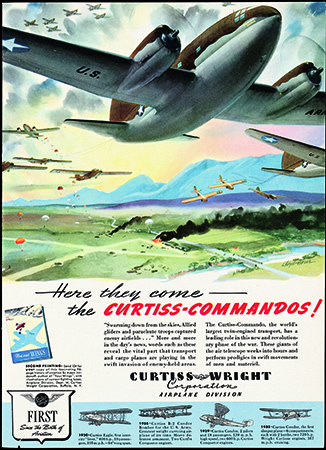

Two other Curtiss-Wright planes played a vital role in World War II: the SB2C Helldiver and the Commando transport. The Helldiver aircraft carrier-based dive bomber was widely used in many of the major Pacific campaigns beginning in late 1943. The Commando became the workhorse of the airlift operation that flew supplies from India over "the Hump," or Himalayan Mountains, to Allied troops in western China.

During World War II Curtiss-Wright and all aviation companies worked in close partnership with the military to build the arsenal of democracy. The output of the company's sprawling airplane, engine and propeller plants across the United States totaled more than 28,000 planes, 130,000 engines and 145,000 propellers, generating more than $1 billion in annual revenue by war's end and making Curtiss-Wright the second largest corporation in America.